The Dismantling of a Financial Watchdog Is Already Harming Consumers—and Worse May Be to Come

With the CFPB told to stop its work, millions of consumers’ hopes of restitution may be lost

Five years ago, Sally Proske was 30 and desperate. She had accumulated nearly $41,000 in high-interest credit card debt—more than she could comfortably pay off on her salary as a live-event and concert production manager in Chicago and still afford rent and food. She knew there was such a thing as debt relief companies and had a vague understanding that they could help her manage and even lower her debt, so she Googled to find one.

She came across a company called Monarch Group and called them. The person she spoke to was sympathetic and struck her as trustworthy—he said that his company had the backing of the FICO credit scoring company as well as the federal government and that it could put her on a repayment plan she could afford. He told her in an email that she had been approved for a “zero interest consolidation” loan and that a partner law firm would help get several thousand dollars of her debt forgiven. If she made monthly payments of $638, he told her, she would be free and clear in four years and boost her credit score, which had sunk to the low 500s.

So Proske signed a contract with Monarch, a subsidiary of a debt consolidation company called Strategic Financial Services, based in Buffalo N.Y. But she didn’t read the contract carefully, and only took a close look at her monthly statements after three years of making regular payments.

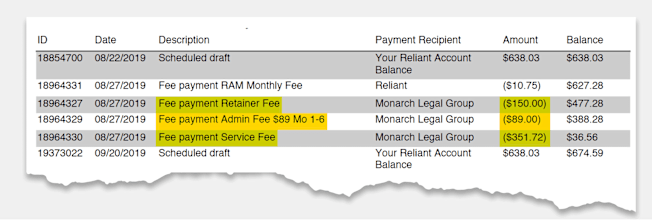

To her dismay, she says, she saw that while she was being charged zero interest and indeed had some of her debt forgiven, a good chunk of each $638 payment she made went to SFS and its law firm for up-front “administrative,” “retainer,” and “service” fees. In total, Proske says she had paid more than $16,000—only about half of which had gone to her creditors. And her credit score was still in the tank.

Graphic: Consumer Reports Graphic: Consumer Reports

Those cases involve several of the nation’s largest financial institutions, including the banks behind the payment app Zelle, over nearly $1 billion in allegedly unchecked consumer fraud on the platform; the bank Capital One, over an alleged scheme involving interest rates on millions of customers’ savings accounts; and Walmart, for allegedly opening accounts for more than 1 million delivery drivers and charging them $10 million in junk fees.

In the SFS case, changes at the CFPB are having an impact already. Last week, SFS attorneys requested that the company’s assets be unfrozen and that it be allowed to collect fees from customers again. They argued that their request should be granted because the CFPB, which had nine attorneys on the case, is now “wholly nonfunctional” and that the idea that the state AGs could continue on their own with the suit was “Pollyannaish.”

“The CFPB is, as we speak, experiencing extraordinary and unprecedented changes,” the company’s attorneys wrote. The judge in the case, U.S. District Court Judge Michael J. Roemer, had denied an earlier CFPB request for a delay to better prepare its case, and the next hearing is scheduled for March 6.

What’s happening with SFS provides the first glimpse into what could be lost when the chief independent consumer watchdog enforcing state and federal laws is shuttered, experts say. The result would be large regulatory gaps, fewer lawsuits brought against companies accused of wrongdoing, and consumers paying more for potentially dubious or fraudulent products in the financial services industry.

“It does not surprise me that SFS is using [changes to the CFPB] to argue that the case is essentially defunct,” says Amy J. Schmitz, a professor and scholar in consumer law at Ohio State University. “Leadership is important and has been one of the key roles for the CFPB since its inception. I believe that others will capitalize on the chaos as well.”

The New York Attorney General’s Office told CR it “intends to continue” the case against SFS; the other six states either declined to comment or did not respond to requests about how they would proceed. The city of Chicago is also suing SFS and Monarch Legal Group, the affiliated Chicago law firm that has enrolled nearly 7,000 consumers in Illinois. While Chicago will continue to pursue its consumer protection case against Monarch and its owner, Timothy Burnette, Chicago’s attorneys told CR they are “disappointed” and “saddened” by news that CFPB could leave their federal case

SFS didn’t respond to CR’s requests for comment but, in court filings, the company has said its clients saved money through its debt relief services, even when accounting for the high monthly fees.

On average, the customers who “graduated” from SFS’ debt repayment program, their attorneys argue, were paying credit card interest rates of 26 percent and had roughly $40,000 in debt spread across eight creditors. “If consumers can only afford the minimum payments, they will never get out of debt,” SFS’ attorneys wrote. “The success of this program must be judged against those alternatives.”

But SFS customer data also showed that roughly 44 percent of clients didn’t complete the repayment program, and ended up paying a higher percentage in fees to SFS as a result.

How Has the Consumer Financial Watchdog Helped You?

Your real-life stories will help us push Congress to stand up for a strong financial watchdog and tough, pro-consumer rules. Share your story.

Restitution in CFPB Lawsuits Often a ‘Lifeline’

In the 14 years since its creation, the CFPB has on numerous occasions imposed steep penalties on companies that fail to follow consumer finance laws and has ordered them to refund or reimburse harmed customers. The agency’s ability to take companies to court is one of its strongest weapons, says Lauren Saunders, associate director of the National Consumer Law Center.

The resulting payouts have been significant. Since late 2021, when former director Rohit Chopra was appointed by President Joe Biden, the CFPB has taken 84 enforcement actions, recouped more than $6.2 billion for consumers, and imposed $3.2 billion in penalties. The CFPB is the primary regulator for banks with more than $10 billion in assets, and it also regulates mortgage companies, payday lenders, and private student loan companies. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the CFPB helped create rules that guard against surprise costs and terms when consumers make mortgage payments and the agency became a key enforcer of laws against deceptive marketing and unfair billing practices by banks.

For consumers, those payouts can be a lifeline. Adam Schnakenberg, who works in trucking outside Chicago, spent five years paying off more than $100,000 of debt to creditors and SFS, cutting back on family vacations, dinners out, and paying off other bills. After years of making payments, and paying nearly $30,000 in fees to the law firm associated with SFS, Schnakenberg discovered that one of his creditors had obtained a court order to garnish his wages. Now, he has medical debts that “need to be paid and the reimbursement of all of those fees would go a long way to making me whole.”

Billions of dollars in reimbursements to consumers are now on the line in the more than two dozen CFPB enforcement cases presently frozen. Judges are not giving the CFPB’s new leadership much time to decide whether to drop each case. Several have deadlines looming in February and March.

Stop the Attack on Consumer Financial Protections

Send a message now to your members of Congress asking them to stand up for consumers, not big banks.

For example, a case involving the bank Capital One, which the CFPB has accused of costing its customers $2 billion by deliberately steering them into low-interest-rate savings accounts, has a hearing scheduled for Feb. 28 in Alexandria, Va. The CFPB had previously tried to delay hearings in the case, to give the agency more time to figure out its next moves. But the judge, U.S. District Judge David J. Novak, wrote in a recent court filing that while he “recognizes that the recent change of administration has impacted the CFPB’s leadership and its work,” he would keep the case moving without further delays. This increases the likelihood that the case could be dismissed entirely because the CFPB is still under a sweeping order not to respond to any judge’s request or offer a defense in any court hearing.

In addition, there are a handful of other consumer protection rules either sitting in federal appeals courts or set to be reversed in Congress. Those rules include capping credit card late fees and overdraft charges, banning unpaid medical debt from being used on credit reports, and limiting the type of financial and personal info about consumers that data brokers can sell.

In the short term, it appears most of the agency’s enforcement cases—at least those without state agencies involved—will be dropped entirely. In those where state attorneys general are involved, as in the SFS case, “it is quite possible [they] will not be able to fill the void left by the CFPB,” says Jeff Sovern, a professor and expert in consumer financial law at the University of Maryland Law School. “Some AGs are not going to be interested in doing that. Others will be but won’t have the resources, especially as they will have to plug holes left by other federal agencies as well.”

The CFPB’s new acting director, Russell Vought, has shut down the federal agency’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. Another Trump administration employee, Mark Paoletta, sent an email to the CFPB’s enforcement staff last week, saying that lawyers shouldn’t work on or make appearances in any existing cases because doing so would be considered “insubordination and we will take appropriate personnel action.”

For thousands of SFS customers, the turmoil at the CFPB is an immediate worry, says Thomas Burt, a partner at Wolf Haldenstein Adler Freeman & Herz, which is representing dozens of clients in cases against SFS. But it could become a concern for many thousands more. “It would be a shame if the gutting of the CFPB allowed SFS to restart their scheme under a different name,” Burt says.

@consumerreports The White House’s latest efforts to undermine the CFPB puts you at risk of falling victim to fraud, scams, and other abusive financial industry practices. Tap the link in our bio to urge your Congressmembers to stand up for you. #cfpb #consumerprotection

♬ original sound - Consumer Reports

Editor’s Note: Our work on privacy, security, AI, and financial technology issues is made possible by the vision and support of the Ford Foundation, Omidyar Network, Craig Newmark Philanthropies, and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.