Scammers Are Stealing Billions From Americans’ Bank Accounts. Here’s What You Need to Know.

A CR investigation found that sophisticated scams targeting bank customers are becoming more common. Yet when the depositors make reimbursement claims, the nation’s biggest banks often deny them.

The phone call that came in at about 10:30 a.m. on a Thursday morning in September appeared legitimate. Cathy M.’s caller ID displayed the number as Wells Fargo’s customer service line, which she had stored as a contact on her phone. Cathy has all calls from unknown numbers sent directly to voicemail. Still, Cathy, a 70-year-old retiree who lives in the Silicon Valley city of Mountain View, Calif., answered the call with some skepticism. She’s gotten enough spam calls to be wary.

Bank Imposter Fraud and Scams Are Surprisingly Common

Bank imposter frauds and scams, resulting in sizable wire transfers of stolen funds, are not new. And Wells Fargo is not the only bank whose customers experience this kind of trickery. But even looking just at Wells Fargo, you can see the size of the problem. In just the past two years, three class-action lawsuits from bilked customers have been filed against the bank in California, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Dozens of other, similar reports of wire fraud scams have been publicized across the U.S.

In one case, a Virginia woman lost her life savings, more than $700,000, in a series of wire transfers made online and in person at a Wells Fargo branch. In another, a Los Angeles woman had $100,000 wired out of her Wells Fargo account after a bank employee was tricked by the scammers.

Phishing schemes, which typically involve criminals sending texts and emails pretending to be a bank or government agency, are proliferating. Since 2019, the number of phishing complaints to the FBI has more than doubled, to nearly 300,000 reports last year, according to the agency’s 2023 Internet Crime Report. And nearly half of all Americans have encountered some type of cyberattack or scam online, according to a nationally representative CR survey of 2,042 U.S. adults conducted in April 2024 (PDF). Of those, 19 percent reported losing money as a result.

Today, scammers—usually working in small teams, each with a specific job, and often operating overseas—are employing increasingly sophisticated cyber tools and using hacked personal data to exploit lingering gaps in banks’ security protocols. In many cases, the cybercriminals are buying so-called “phishing-as-a-service” cybercrime kits and subscriptions—a one-stop shop of tools, templates, and services made specifically for criminals so that they can more quickly and easily lure bank customers and steal their money. The kits, available on the messaging app Telegram and on the Dark Web, can be purchased as a subscription for as little as $150 a month and have bizarre names, such as Anthrax, the ONNX Store, and Darcula.

Banks are struggling to keep up, despite spending billions of dollars each year on anti-fraud measures. They are also denying wire fraud claims from their customers, citing the Electronic Fund Transfer Act. That federal law doesn’t require banks to reimburse customers when they are tricked and end up authorizing money to be sent to scammers. Rather, the law requires banks to make their customers financially whole only in limited circumstances—like when a cybercriminal gains unauthorized access to their accounts after finding or stealing someone’s phone.

“Financial institutions across the board are not reimbursing consumers, even when it appears the wire transfer request was not done by the consumer but someone who gained access to the consumer’s account and initiated the wire,” says Carla Sanchez-Adams, a senior attorney at the National Consumer Law Center who focuses on emerging issues with banking. “In other words, even where the weak law provides some remedy for a consumer for an unauthorized wire, the financial institutions fight tooth-and-nail to hold the consumer liable.”

“Once the money is transferred from your account, you have not days, not hours, but minutes to report it, to have hope of getting something back,” says Thomas W. Cronkright II, the co-founder and executive chairman of CertifID, a company that works with government agencies and companies on fraud cases.

A proposed amendment to the law, called the "Protecting Consumers from Payment Scams Act," would require banks to share the financial liability for such frauds when the customer is “induced” into sending criminals money. In 2023, three of the country’s largest banks—JP Morgan Chase, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America—reimbursed their customers for scams at relatively low rates: 2 percent, 4 percent, and 24 percent, respectively, Senate investigators found.

“The banks are aware that, every single day, some of their customers are going to be hurt,” says Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) in an interview with Consumer Reports. “But they are failing to protect consumers from threats. They fail to prevent the frauds. And then they refuse to reimburse consumers when the speed and irreversibility of these transactions causes their consumers to be duped.”

The American Bankers Association, of which Wells Fargo is a member, along with other banks, has opposed the proposed change. Wells Fargo has argued that by reimbursing all types of fraud, it could incentivize some customers to game the system by reporting losses they never incurred, Adam Vancini, the head of Wells Fargo’s payments department for consumer, small, and business banking, said during a July Senate congressional hearing in response to questions from the ranking Republican member, Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.). In response to the proposed legislation, the bankers’ group countered with a call to develop a national fraud and scam strategy relying on better law-enforcement tools along with a streamlined way for consumers to file complaints. The fraud and scams bill is currently under consideration by the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, but it faces long odds with Republicans, who have expressed reservations about the amendment and are taking majority control of the Senate in January. Johnson said during the July hearing that he thought current anti-fraud safeguards used by banks “work pretty well.”

Wells Fargo also says it alerts customers to possible scams in multiple ways, by text, email, and within mobile apps. U.S. banks have implemented their own closely held anti-fraud tools, including instituting “dynamic limits” for things like first-time transactions, which can limit the amount a customer is able to send, or by sending a pop-up question asking about the purpose of certain transactions that they deem risky.

But there is a solution that would likely reduce many cases of wire fraud, regulators say. In Cathy’s case, a temporary hold on the funds—freezing them in the account for just one to two business days—would have given her and Wells Fargo time to identify the fraud and reverse the wire transfer. But because Wells Fargo allows many wire transfers to process, often within minutes, as other banks also do, the money moved too quickly for anyone to catch it.

In response to questions from Consumer Reports, Wells Fargo reopened Cathy’s reimbursement claim but ultimately denied it because she had given the scammers her account login credentials. “Monetary recovery or reimbursement for scams is unlikely in most cases,” Wells Fargo said in a statement. “We deeply empathize with those affected by financial scams and understand the significant emotional and financial toll falling for a scam has on the victims. Safeguarding our customers’ assets is our top priority. We have robust security measures in place and conduct thorough investigations when fraud or scams are reported.”

But despite their fraud prevention and security efforts, Wells Fargo is reimbursing customers at lower rates now than they did just a few years ago. Filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission show the bank reimbursed its customers for fraud at a lower amount in 2023—about $207 million. In 2021, that figure topped $500 million.

Cathy reported the scam to the three federal agencies that handle wire fraud cases: the Federal Trade Commission, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the FBI. In addition, California’s Attorney General’s Office investigates financial fraud and phishing scams and, in a statement to CR, said they “pose significant risks to consumers and we are deeply concerned about these reports.”

Once the money is transferred from your account, you have not days, not hours, but minutes to report it, to have hope of getting something back.

Where the Stolen Money Goes

The typical wire fraud now includes multiple elements of “social engineering”—psychological tricks criminals use to earn your trust and cooperation. In Cathy’s case, reading back her Social Security number led her to believe the scammer was a real bank employee.

Then, in a process anti-fraud experts call “money muling,” the scammers transfer the stolen funds to other accounts in the U.S. and abroad, making it difficult for banks to find and claw the money back.

The owners of these other accounts are often paid intermediaries who help cyber gangs move money quickly and confuse law enforcement agencies, says Cronkright of CertifID.

In Cathy’s situation, the money stolen from her account was transferred to the account of a man who lives in South Florida, CR found. It’s unclear if the Florida account owner was actually involved with the wire fraud and he hasn’t been charged with a crime in connection with Cathy’s case, so CR is not identifying him. But CR did track him down and asked about the transaction. He did not respond to our requests for comment.

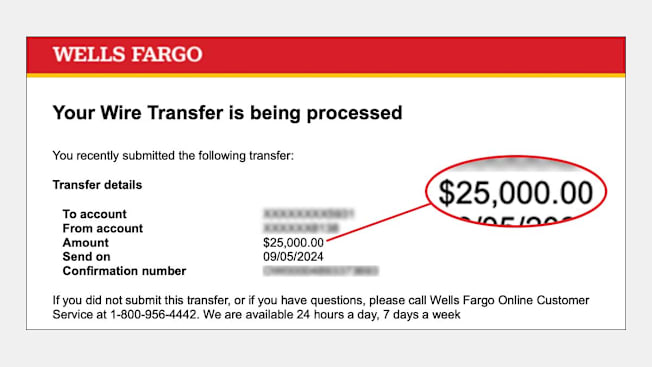

Source: Courtesy of Cathy M Source: Courtesy of Cathy M

To help convince their victims they are real bank or government employees, cybercriminals are purchasing hacked or leaked customer data—Social Security numbers, bank account details, and purchase histories—for as little as a few cents per person. They are also pursuing specific targets as opposed to sending out emails en masse. For example, residents of Santa Clara County, Calif., where Cathy lives, filed the most phishing scheme reports of any county in the U.S. last year, and the FBI’s San Francisco field office has been inundated with similar kinds of fraud. The reason for cyber criminals focusing on California’s Bay Area? That’s where the money is, in terms of wealthy potential victims.

Slowing down the money transfer process for high-dollar or suspicious transactions would likely go a long way toward curtailing such fraud. In cases where wire fraud is $50,000 or more, the FBI can initiate what it calls a “Financial Fraud Kill Chain” request, which freezes the money in bank accounts so that it can be returned to the customer. But in order for the FBI to begin that process, the request has to be filed no later than 72 hours after the original, fraudulent wire transfer.

Beyond that, the legislative changes sought by House and Senate Democrats would require reimbursement by banks for all types of fraud—whether the customer pushed the button to send their money or not. That, in turn, would force banks to implement stronger security measures to help reduce the amount of fraud flowing through their systems, and the resulting financial liability, experts say.

In the United Kingdom, under a law that went into effect on Oct. 7, 2024, banks are now required to pay up to 85,000 pounds, or approximately $108,000, to reimburse imposter scams that use "push payments" through banks, including those who unintentionally authorized a payment to a criminal. How the fraud reimbursement process works there could influence future changes to U.S. banking laws, said John Breyault, who manages the National Consumers League’s Fraud Center.

The first report on the U.K. bank reimbursement law, and its effect on consumers, is expected sometime next year.

Tips to Protect Yourself From Online Fraud and Scams

Protect your information. Never give anyone who contacts you—whether by email, text, phone, or in-app message—your bank account info or login credentials. Imposter scammers can pretend to be your bank, a government agency, law enforcement, or even your family and friends. Instead, end the communication and call the institution or person by phone to ascertain the validity of the need for the information.

Use secure payment methods. Don’t send money for goods and services using payment methods such as Venmo, Zelle, gift cards, or cryptocurrencies, as it may be nearly impossible to get your money back in case of fraud. Use credit cards or other payment services, like PayPal, which have longstanding protections against fraud and theft.

Be careful when you send money through a bank or wire transfer. As wire transfers can process within minutes, it can be difficult to trace where your money goes. Always verify who you’re sending money to and take your time before sending large amounts of money to anyone.

Keep your guard up. Be mindful of anyone who uses methods of persuasion to get you to do something like send money. These psychological tricks can take many forms, including pressing you to act fast or using threats to scare you.

Keep open lines of communication about money with friends and family. It can be a taboo subject for many people, and older Americans might be especially hesitant to discuss their finances even with the people closest to them. But many consumers can avoid sophisticated financial schemes and traps when they’re suspicious simply by having someone to confide in.

Think about what you post publicly online. The more information you have about yourself online, the more material a scammer has to work with when crafting a personalized cyberattack. You can keep your social media and LinkedIn accounts but be circumspect about the personal information you disclose on them.

Editor’s Note: Our work on privacy, security, AI, and financial technology issues is made possible by the vision and support of the Ford Foundation, Omidyar Network, Craig Newmark Philanthropies, and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.